A recent redefinition of multiple myeloma (MM) allows patients to be diagnosed and treated before they show signs of the disease’s most problematic characteristics. The new guidelines also lift the burden of what to do with some patients who were considered to have smoldering MM (SMM) but now fall into the category of MM.

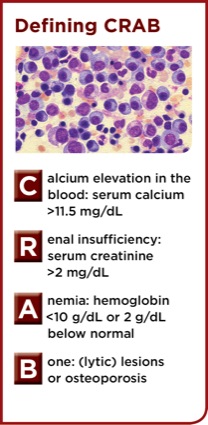

The guidelines, authored by members of the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG), represent a paradigm shift away from an era in which patients needed to show end-organ damage, hypercalcemia, anemia and bone lesions (i.e., CRAB features; see box) before their condition is considered a cancer and treated as such (Lancet Oncol 2014;15[12]:e538-e548, PMID: 25439696).

“The criteria now allow early diagnosis, prior to symptoms,” said S. Vincent Rajkumar, MD, a professor of medicine at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn, and the lead author of the guidelines.

The new guidelines add three new criteria to the existing definition of MM. These new myeloma-defining events are the presence of 60% or more bone marrow plasma cells, abnormal free light change ratio of 100 or more and more than one focal lesion found on magnetic resonance imaging.

“These three new multiple myeloma–defining events were adopted based on evidence from two or more independent studies showing that their presence is associated with an ultra-high risk of developing end-organ damage from the malignancy (approximately 80% within two years), that there was no major reason to delay therapy for such patients, and that treating such patients would prevent serious end-organ damage,” Dr. Rajkumar said.

The IMWG also clarified that bone disease in MM can be determined not just by skeletal survey but also by computed tomography (CT) or positron emission tomography CT scans, and that renal disease can be identified not only by serum creatinine levels but also by creatinine clearance.

“As a result of all these changes, we believe that myeloma will be diagnosed in a timely manner and that patients will be spared the trauma of having to wait until organ damage happens before therapy can begin,” Dr. Rajkumar told Clinical Oncology News.

Earlier Treatment for SMM

With the redefinition of MM, the definition of SMM has changed as well. Patients are now considered to have SMM if they have 10% to 60% clonal plasma cells without evidence of CRAB or other MM-defining characteristics.

The rationale for this update in definitions stemmed from the fact that MM remained unique among cancers in that it required patients to develop end-organ damage before they could be diagnosed and treated. “Part of the reason myeloma lagged behind was the thought that many patients with SMM could go years without needing therapy,” Dr. Rajkumar said. “Another concern was over the toxicity of the treatment.”

Today, however, both concerns are mitigated by the fact that researchers have identified biomarkers to more accurately pinpoint which SMM patients are likely to progress, and that current therapies are well tolerated and can more than double the survival of MM patients.

“Also, we had a randomized trial in high-risk SMM patients that showed early therapy can improve survival, further alleviating concerns about overtreatment,” Dr. Rajkumar said, referring to a Spanish trial that compared lenalidomide with observation (N Engl J Med 2013;369[5]:438-447, PMID: 23902483).

With the bar lowered for diagnosing MM, some of the controversy over what to do with SMM patients has lightened. “The highest-risk SMM patients are now considered multiple myeloma patients,” Dr. Rajkumar said. “The extension of the multiple myeloma diagnostic criteria takes the pressure off treatment decisions for patients with SMM, but there will still be some patients for whom we are nervous about waiting and watching,” Dr. Rajkumar said.

The median interval to progression for SMM patients is approximately five years, although it varies considerably in this heterogeneous population. The patients who cause concern are those at risk for progressing to MM within two years, and they are identifiable by a number of risk factors. “There is the size of the monoclonal protein, the proportion of plasma cells in the marrow, the immunophenotype of these plasma cells, the suppression of uninvolved immunoglobulins, the proliferative rate of the plasma cells and cytogenetic abnormalities,” Dr. Rajkumar said.

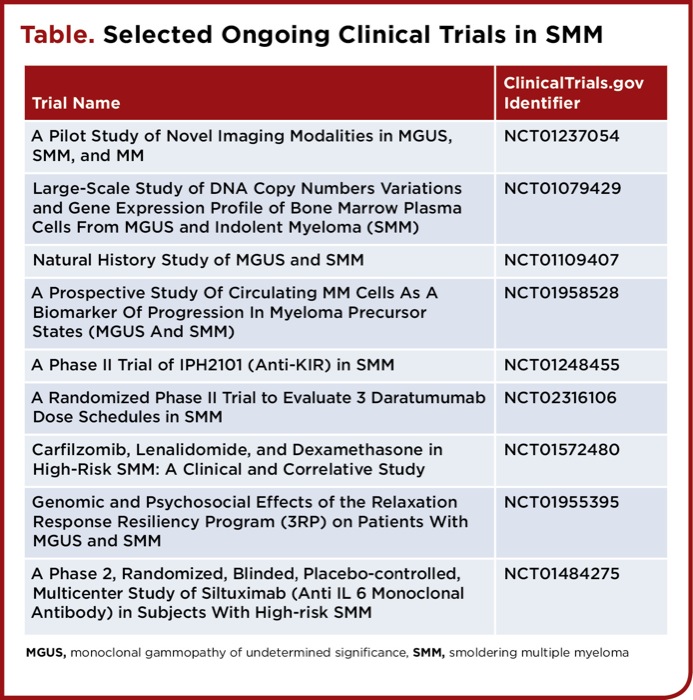

“In patients with SMM who have multiple high-risk factors, we do wonder whether or not to treat. The standard of care remains observation, and clinical trials are preferred. There are two schools of thought on this. One is to do prophylactic therapy with one or two agents to try and delay progression, and the other is to go ahead and treat them as myeloma patients.”

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

That said, Dr. Rajkumar said that he suspects very few SMM patients will require treatment. The recommendation for the rest is observation or enrollment in clinical trials. “The reason for that is that we really need data that such patients will benefit from early therapy, more data than the Spanish trial gave us,” Dr. Rajkumar said.

Syed Abutalib, MD, an assistant director of the Hematology and Stem Cell Transplant Program at the Midwestern Regional Medical Center, in Chicago, is generally in support of the new guidelines, particularly regarding the redefinition of MM, but he cautioned that there are some unanswered questions about SMM. “There still needs to be work done to identify ‘high-risk’ groups of patients who are identified as ‘smoldering’ MM patients, even with the new guideline. Due to well-recognized biological and clinical heterogeneity, certain proportions of patients with SMM still have a more aggressive disease course.” he said. “No doubt, the so-called ‘ultra-high-risk SMM’ has been grouped with MM, which makes it low-risk MM (considering tempo of the disease only), but still there is a high-risk group that needs to be dissected out from the new definition of smoldering MM.”

Dr. Abutalib also concurs with the guideline’s recommendation that SMM patients should not undergo treatment and should be handled by observation or preferably, in his opinion, enrollment in clinical trials. “We cannot improve on outcomes,” he said, “unless patients are enrolled in well-constructed clinical trials.”

Emphasizing the complexity of this area, he said all patients with SMM should be given the opportunity to seek advice from a myeloma expert. “Selection of a clinical trial among numerous options is not easy. When you have so many options, it makes you wonder—if there is such a lack of consensus among experts, how do you make the right choice? Additionally, it makes the patient nervous and definitely does not make it easier for the community oncologist, the primary referral source.”

It is prudent that oncologists selecting a trial keep in mind the needs of their patients, carefully calculate the risks and benefits and fully understand what the trial is trying to achieve (e.g., primary end point, duration of therapy, type of therapy), he said. “You have to select the trial that best suits your patient’s need, and the toxicity of any intervention should be balanced with primary outcome.” Although the drugs may have improved, he said, there is still toxicity, and there are other factors to consider, such as inconvenience to the patient and impact of the therapy on quality of life.

Drs. Rajkumar and Abutalib reported no relevant financial relationships.