By Sarah Tilyou

Enough evidence has trickled in to support the use of the investigational antiviral remdesivir in patients with COVID-19 that the FDA has issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for the drug in that setting, but experts underscore that the data remain preliminary and need to be confirmed.

The EUA allows remdesivir—being developed by Gilead—to be distributed in the United States and administered by health care providers to treat hospitalized patients with suspected or laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 that is defined as severe based on low blood oxygen levels or the need for oxygen therapy or more intensive respiratory support (bit.ly/2Su349P).

The FDA issued the EUA two days after National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) investigators released positive preliminary findings from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial of the drug. In the trial, hospitalized patients with advanced COVID-19 who received remdesivir recovered faster than similar patients who received placebo.

The trial—called Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial (ACTT)—began on Feb. 21 and includes 1,063 patients at 68 sites—47 in the United States and 21 in countries in Europe and Asia (bit.ly/3aRIyWR; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04280705). In the study, patients are treated with 200 mg of remdesivir on the first day of enrollment and 100 mg per day on up to nine subsequent days of hospitalization (maximum, 10 days), or placebo.

Preliminary Analysis Shows Benefit

An independent data and safety monitoring board overseeing the trial conducted a preliminary data analysis that indicated remdesivir reduced time to recovery—the primary end point—better than placebo. Recovery was defined as being well enough for hospital discharge or returning to normal activity level.

Patients who received remdesivir had a 31% faster time to recovery than those who received placebo (P<0.001). Specifically, the median time to recovery was 11 days for patients treated with remdesivir compared with 15 days for those who received placebo. The results also suggested a trend for a survival benefit, with a mortality rate of 8.0% for the group receiving remdesivir versus 11.6% for the placebo group (P=0.059).

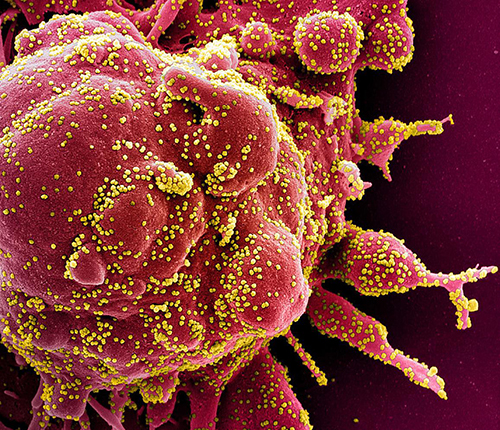

Source: NIAID.

The early placebo-controlled results support positive findings from an uncontrolled compassionate use trial of the drug reported in mid-April (bit.ly/2YqnxjI), but they contrast with findings from a placebo-controlled trial of 237 Chinese patients that showed “remdesivir was not associated with statistically significant clinical benefits” (Lancet 2020 Apr 29. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31022-9).

Early NIAID Study Results ‘Encouraging’

Jeffrey R. Aeschlimann, PharmD, an associate professor at the University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy, in Storrs, and adjunct associate professor at UConn School of Medicine’s Division of Infectious Diseases, in Farmington, called the results from ACTT “very encouraging.” Noting that “a therapy that can potentially make patients improve quicker and get discharged from hospitals will be an important advance to decrease strain on our health care system [and] support eventual easing of social distancing measures,” he nevertheless expressed tempered enthusiasm for the drug based on the mechanism of action and limited data available at this point.

“We all would love to have seen remdesivir, or any drug for that matter,” cause mortality rates “to go from the placebo number (approximately 12%) to something like 1%, but it’s unrealistic to expect a drug only with antiviral activity to do this,” Dr. Aeschlimann said. “By the time patients need hospital care, the downstream effects of the viral infection have kicked in. We know that there’s an excess of unhealthy immune system activation, lung tissue damage, and strain on an already chronically ill patient’s heart, kidneys, liver and other vital organs.” In addition, he pointed to the “large role of hypercoagulation in the morbidity and mortality of COVID-19–infected patients.”

However, the findings of the trial do offer some cause for optimism. The inclusion criteria “required a patient to be pretty sick,” Dr. Aeschlimann said. “So in that context, an approximately 4% reduction in mortality (an approximately 33% relative decrease) potentially could be pretty good. Although it didn’t reach our standard P value for statistical significance, it came pretty close (P=0.059). Given the reported sample size of 1,063 patients, if you play around with projected numbers, all it would take is a change in one or two deaths in each group to make that P value less than 0.05,” he noted.

Although the trial conducted in China was not supportive of remdesivir, it had an important limitation in that it was terminated early, mainly due to an inability to recruit patients once the pandemic waned there. So, Dr. Aeschlimann said, “it was severely underpowered to assess the primary end point (58% power, per the manuscript)” and did not do much to clarify the picture.

One finding from the Chinese trial that Dr. Aeschlimann called “interesting and discouraging” was that remdesivir did not result in a “significant change in the time profiles of SARS-CoV-2 viral loads,” despite showing “potent in vitro activity” and an ability to “reduce viral loads in a primate model” of COVID-19. But “this doesn’t mean that remdesivir has no antiviral activity in humans,” he said.

He speculated that the lack of significant change in viral load time profiles could be related to two factors: the timing of initiation of therapy and the sensitivity of viral detection. Regarding the first factor, it may be that “maximum benefits would be derived from starting treatment as early as possible in the disease process.” In the Chinese trial, patients had a median of 10 days of symptoms before admission. “That may be too late in the infection process to have potent effects on viral replication,” he said. Data that Gilead released from its SIMPLE trial support that idea, “with better results in those started earlier on the drug” (see sidebar). Regarding the viral detection methods used in the Chinese trial, Dr. Aeschlimann said that “assessing and detecting amounts of shed viral RNA into the upper and/or lower respiratory tract secretions—without determination of its viability and/or infectivity potential—may not turn out to be the most sensitive or specific marker of in vivo antiviral activity.” He added that “there may be other ways that we have yet to discover/implement that could show antiviral activity.”

| Five- and 10-Day Remdesivir Dosing Yielded Similar Efficacy

“These data are encouraging as they indicate that patients who received a shorter, five-day course of remdesivir experienced similar clinical improvement as patients who received a 10-day treatment course,” said Aruna Subramanian, MD, the chief of immunocompromised host infectious diseases at Stanford University School of Medicine, in California, and one of the lead investigators of the study. “While additional data are still needed, these results help to bring a clearer understanding of how treatment with remdesivir may be optimized, if proven safe and effective.”

|

Production Will Need to Be Ramped Up

Although the remdesivir evidence still is preliminary, it was enough to convince the FDA to issue the EUA. As a result, Gilead will need to dramatically accelerate production to meet global requirements. The FDA “has been engaged in sustained and ongoing discussions” with the company about “making remdesivir available to patients as quickly as possible, as appropriate,” according to NIAID.

In an open letter on Gilead’s website, CEO and Chairman Daniel O’Day noted that the company has “been ramping up production since January, working within all the constraints [of the] lengthy and complex manufacturing process” required to make the drug (bit.ly/2Yq2cH6). “Existing supply, including finished product ready for distribution as well as materials in the final stages of production, amounts to 1.5 million individual doses,” Dr. O’Day noted. Based on a 10-day course of treatment, the company had estimated that to be approximately 140,000 treatment courses, but if a five-day course turns out to be effective, as early findings from the SIMPLE trial indicate (see sidebar), that could potentially double the number of patients treated.